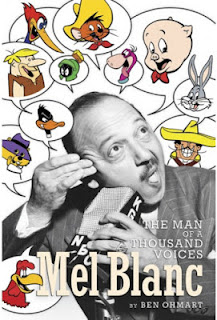

In 1935, sensation surrounded the opening of Warner Bros’ newest film, G-Men. In the film, James Cagney did not play the “tough guy gangster” for which he was known, but rather a federal lawman. A press release for the event read: “Hollywood’s Most Famous ‘Mad Man’ Joins the ‘G-Men’ and Halts the March of Crime!” When Phillips H. Lord returned to New York that same year, he was flat broke. He had no idea what to do next. He was also heavily in debt. Walking up Broadway he happened to notice a big sign on a theater advertising the Warner Bros. movie

|

| 1943 movie poster |

The gangster-hero of early Depression films – the self-made individual who defied an apathetic government and inept police in his quest for success – had previously enjoyed immense popularity in such films as The Public Enemy (1931) and the F.B.I.-endorsed movie You Can’t Get Away With It (1936). The latter film was a documentary-style short showing the inner workings of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, with permission from the Honorable Homer S. Cummings, Attorney General of the U.S., and with the cooperation of J. Edgar Hoover, appearing as himself, giving his G-Men orders to apprehend the criminals at large.

Puzzled, Lord asked, “What are G-Men?” Lord had been away for two years and the name G-Men was practically unknown when he left the U.S. After an explanation, he said, “what a great radio show that would make!” He walked up the street thinking it over. Cagney’s new role as a “government man” was a sign of the overall shift taking place in the minds of the public about law enforcement as well as the efficiency of the entire democratic system itself. Hundreds of thousands of others had seen that name, just passing by, and it took Lord who was broke and out of broadcasting to recognize the possibilities and do something about it. The next morning he called the Chevrolet/General Motors Company and went to see one of their officials. The outcome was that after three days of negotiations, he walked out of the National Broadcasting Company with a personal contract in his hands.

MUSIC: (Orchestral Chord Sustained)

ANNOUNCER: Presenting the first of a new series of programs … G-Men!

MUSIC: (Orchestra Plays … 15 seconds … music softens)

SOUND: (Woman’s Shriek)

MAN’S VOICE: Stop her!

SOUND: (Two quick shots)

SOUND: (Door Slams)

MUSIC: (Orchestra up full … 15 seconds … stops)

SOUND: (Two sirens fade in and out in succession)

SOUND: (Hollow-voiced police calls)

POLICE: Calling cars 42, 23, 56 report immediately – Police Headquarters. Calling all cars…cover all roads leading from the city for two black sedans. Calling (fade) all cars … cover roads from city.

THREE NEWSBOYS: Extra … Extra … All about the Dillinger gang … Read about Dillinger shooting way to freedom … Extra … Dillinger and Baby-Face Nelson!

SOUND: (Calling of newsboys fades)

ANNOUNCER: Chevrolet presents tonight the first program in its new series – G-Men – Every fact is taken from the files of the Federal Bureau of Investigation United States Department of Justice, at Washington. Tonight’s program is not a story. It is an accurate account of the hunt for John Dillinger by our G-Men. And now I present Phillips Lord, the creator and director of this series.

LORD: Good evening. This series of G-Men programs is presented with the approval of the Attorney General of the United States and J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Department of Justice. Every fact in tonight’s program is based upon information in the files of the department. I went to Washington, was graciously received by Mr. Hoover, and all of these scripts are written in the department building. Tonight’s program was submitted to Mr. Hoover, who checked every statement and made some very valuable suggestions.

|

| Phillips H. Lord |

The photo above is courtesy of the Phillips H. Lord family. This same photo has been adjusted and color tinted (a.k.a. altered) on a number of web-sites. The photo above is offered in its purity, with no alterations performed except for a clean tiff and jpg scan.

In a press release dated July 14, 1935, it was clear that the G-Men were now a viable property appropriate for dramatic exploits: “A new weekly dramatic serial, G-Men, based on actual cases from the files of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, opens coast-to-coast Saturday night at 8 o’clock, EST. The continuity will be prepared by Phillips H. Lord, known on the air as Seth Parker. ‘If there are some who are still dazzled by the false glamour of the gangster,’ said a representative of the sponsor, ‘we hope these radio programs will show little glamour is left to the criminal, when he comes to the end of the road.’ The purpose of the broadcasts, it is pointed out, is to ‘holdup a clear mirror to the “G” man and his activities, and let the true reflection, as contained in the official records, speak for itself.’ By extending accurate workings of the department it is hoped, through these broadcasts, to ‘double the effectiveness of this arm of the government by increasing public cooperation in the war on crime’.”

G-Men premiered on July 20, 1935, with a crime dramatization about former “Public Enemy Number One,” John Dillinger. His daring escapades in crime, his brush with the law, and total disregard for society were highlighted on the program. A recreation of his death on the streets outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago was also dramatized, the climax of the premiere broadcast, emphasizing that “crime does not pay,” a moral that radio listeners would be reminded of for the next twenty years.

For the second broadcast, “The Case of ‘Baby-Face’ Nelson,” the needless killing of Special Agent G-Man Carter Baum was dramatized, revealing just how cold-blooded and heartless the week’s top villain was to the American public. Radio listeners paid careful attention to the Department’s methods of investigation, and its pursuit of Nelson toward Lake Geneva, where G-Men attempted to apprehend “Baby-Face.” Towards the finale, G-Men took a stand and shot it out with Nelson, who collapsed, having been shot 17 times.

|

| Gang Busters comic book |

The broadcast was as authentic and true to the facts as it could possibly be. Inspector Samuel Cowley, who was the chief investigator during the two broadcasts, was accurately depicted as the man responsible for the death of the two notorious figures. Although Purvis spent a lifetime claiming he killed Dillinger, the shots were fired by Cowley and other F.B.I. Agents. Cowley and another Agent, Herman Hollis, four after the death of Dillinger, shot it out with Nelson and a confederate, John Paul Chase. Bother agents were killed but had managed to wound nelson seriously and he died within days. Hoover himself (appearing by proxy) praised the fictitious Cowley for his bravery after the “Baby-Face” Nelson drama. “There’s your two kinds of men,” Hoover told the radio audience. “Cowley gave his life to protect others; he’s loved, honored, respected. Nelson hated, despised; even his body discarded into the mud of the gutter.”

Hoover’s actual involvement with the scripts was minimal, but it appears not a single script didn’t receive some change or suggestion, even if it was a couple words. Case in point, “The Fleagle Fingerprint Case,” where on page 24 (second line of the teaser for next week’s program) read: “which will include the spectacular escape,” Hoover added “and eventual death.” These three words were inserted between the words “escape” and “of.” Hoover’s endorsement of the G-Men program was another example of how he loved publicity, and seeing his name in the papers.

G-Men receiving the distinction of having Hoover endorse the program was more or less a privilege. During the months G-Men gained popularity, Hoover returned a check for $1,500 to the American Magazine, which had sent him an article he had apparently allowed a writer to prepare and publish under his name. Having reviewed the article, he turned the offer down.

In late September of 1935, Dick Tenelly, radio columnist for the Washington Daily News, a local writer having no connection with the Associated Press, attempted to make a name for himself by the cynical “slamming” of new radio programs. His opinion was thought of very lightly by other critics as well as radio people. The article caught the eye of J. Edgar Hoover, who checked on Tenelly’s comment that the National Women’s Radio Committee thought of the series as “sissy,” and immediately composed a letter suggesting he withdraw all cooperation of the Department regarding the program.

On September 14, 1935, Phillips H. Lord wrote the following reply: “This series, Mr. Hoover, means more to me than anything else in the world. My whole future will be based on the success of this program, and there isn’t a stone I’ll leave unturned toward making it the finest thing in radio. If you can spare a few minutes next week to talk with me, I feel that I can save you the greater part of this worrying you have been through. Thus far, everything has been done through a third party and I have only gotten part of an idea of what you had in mind. Almost every radio program that goes on the air is severely criticized by the newspapers. The newspapers resent radio taking advertising from them, and, three years ago, there was quite a stiff battle between these two mediums. That has practically blown over, but the radio editors do pick on opening series. The reason for this is that, if they criticize programs which have been running for a long time too harshly, the fans of the program become incensed and make it very unpleasant for the radio editor. The result is that most of the severe criticizing is done of the new programs until the program gains its following; thereby establishing itself, as it were. In spite of this situation, however, we have had many times as many favorable comments as we have unfavorable.”

|

| Phillips H. Lord. Photo courtesy of Joel Walsh. |

Phillips H. Lord found little cooperation from employees of the radio broadcasters because of his association with the Seth Parker incident, until the success of G-Men, claiming that “important people always had to put up with adverse notoriety from envious or otherwise disgruntled people.”

In the third broadcast of the series, the famed Osage Indian Murders were presented with a certain stark realism. Between 1921-23, several members of the Osage Indian Reservation died under suspicious circumstances. William “King of Osage” Hale was suspected of being involved in the deaths, and agents posing as medicine men, cattlemen and salesmen infiltrated the reservation and eventually solved the murders. Hale had committed the murders in an attempt to collect insurance money and gain control of valuable oil properties owned by the deceased, a true narrative that had the sound and fury of a wholly dramatized script for a competing radio detective series.

One script written about “Shoe Box” Sal was not approved by the Department. Their reason was because nothing in the script tied in any way to the Federal Agents. Scripts written to dramatize the exploits of Dutch Schultz and Ma Barker and her boys were composed, but neither of them were dramatized on the G-Men series. For the broadcast of October 12, 1935, G-Men presented “The Case of Eddie Doll.” Originally this was going to be a script about the O’Malley bank robbers and the August Luer Kidnapping, but when the facts of the case revealed that O’Malley had nothing to do with the Million Dollar Robbery, the notion to script the daring exploits of O’Malley got shelved. Besides, the trial for the double bank robbery was scheduled for the very day this broadcast took place, and it might have hurt the prosecution if too many facts were divulged prior to the trial. Instead, a script about Eddie Doll, who committed three daring bank robberies, a sensational mail robbery and a kidnapping, was dramatized.

“I’ll never forget the first broadcast I ever took part in one of Mr. Lord’s scripts,” recalled Helen Sioussat, Lord's secretary. “I was so careful about preparing, that every word was written and counted and rehearsed. We had been told that because an important sports broadcast had run over its time, our talk would be postponed half an hour, and we were sitting chatting happily – when all of a sudden someone told us that instead we were going on immediately. We rushed to the table mike and spread out our manuscript. As we went on the air, the production man whispered to me that we would have to cut two and a half minutes out of our talk! So there we were on the air, and I had to actually ad lib. This was my first broadcast and at the same time I had to reach over and cross out whatever M. de Chatillon had that I thought might be dispensed with, to keep continuity of thought and yet end on time. All I could do was hope he could follow my pointing. Somehow he did – somehow we finished – and I actually got my first fan mail, from a rather helter-skelter few minutes!”

On September 21, 1935, Dr. Tyler, Executive Secretary of the National Committee on Education by Radio, paid a visit to Lord’s office. Although he had never heard a broadcast of G-Men, he had received numerous complaints about the program, most of which he attributed as cranks, as they objected to the programs for the reason that they brought the subject of “crime” before the youth of the country. After an hour-long conversation regarding the purpose of the programs, how they were designed to supply an antidote, in order that they be given the right conception of which civil authority outweighed the pattern of crime, with the moral that “crime does not pay,” Dr. Tyler left the office satisfied as to the sincerity of the purpose of the G-Men programs. Mr. Linthecum, Fraternal Editor and Assistant Sunday Editor of the Star, simply raved about the realistic, thrilling programs of G-Men. He said he wouldn’t miss one for the world. Mr. Collier received several complimentary remarks made to him about the series by newspapermen, who, as a rule, were rather noted for their severe criticism. A brief in a September 1935 issue of the Sunday New York Mirror claimed that G-Men outranked The March of Time, in their estimation.

During that same month, Braddock, the heavyweight champion, met with J. Edgar Hoover personally in Washington. As soon as Hoover met them, he brought up the subject of G-Men and how splendid were the last two programs. He even preferred the Kelly case. Dr. James A. Bell, President of the South Eastern University Law School, listened to the program for the first time, hearing the Kelly Case, and expressed his opinion to the folks at Lord’s office that he thought it was the best thing on the air. “My wife and I got so thrilled and excited,” he told them, “that we will never miss another program, and we are both sick to think that we have missed the preceding ones.”

On September 9, 1935, Sioussat wrote to John O. Ives from Washington, D.C.: “Just at this time the Department would start waking up to the fact that G-Men is a wonderful series and especially for them. It’s too bad they didn’t realize it before and save us all the headaches we’ve had since they started ‘cooperating’ with us.”

Early production notes suggest that Lord adhered to strict policies when it came to the content of the programs. “Every criminal mentioned must be killed or corrected,” was one of the rules. Agents of the Department, it was explained during one of the broadcasts, had no pension rights because they were not under civil service; hence when a G-Man was badly wounded, killed or retired because of age, his family must get along as best it could (remember, this was 1935). The program also reported that widows of men killed in the line of duty were offered employment at the Bureau to help aid in financial support and according to one report, there were at least four of them in 1934.

Phillips H. Lord owned a directory (issued February 1, 1935) of the Division of Investigation U.S. Department of Justice, Washington D.C. with all room numbers and telephone numbers and extensions of personnel involved (which included Tax and Penalties Unit, the Crime Laboratory, Training Schools, Mail Room, Personnel Files, Field Administration, Chief Clerk, Messengers, Notary Public, Rifle Range, Switchboard, Department Officials, and so on). This directory came in handy when, during the final stages of scriptwriting, technical details could be made accurate with the ease of a phone call.

The following is an episode guide for all 13 "lost" radio broadcasts, the precursor to the famed Gang Busters radio program. According to Jay Hickerson's Ultimate Guide, none of the 13 radio broadcasts are known to exist.

EPISODE #1 “THE CASE OF JOHN DILLINGER”

Broadcast on July 20, 1935

Script written and completed on July 13, 1935.

Plot: John Dillinger was known as Public Enemy Number One. Although he committed the most serious crimes, they were all state offenses and the Department of Justice did not have the authority to go to work until March 3, 1954 when Dillinger escaped from jail at Crown Point, Indiana, and stole an automobile at the prison gates, in which to make his escape. The stealing of that automobile and driving it across the state line was a Federal Crime and the G-Men went into action.

EPISODE #2 “THE CASE OF ‘BABY-FACE’ NELSON”

Broadcast on July 27, 1935

Plot: With the killing of John Dillinger, “Baby-Face” Nelson became Public Enemy Number One. “Baby-Face” killed a Special Agent, G-Man Barter Baum. Following Dillinger’s death, Inspector Cowley directed the hunt for Nelson, a former member of the Dillinger gang. On February 17, 1932, Nelson escaped custody of a guard on his way to the Illinois State Penitentiary. Inspectors Crowley and Hollis raced toward Lake Geneva, hoping to meet up with other Special Agents, in an attempt to apprehend “Baby-Face” Nelson. The police took a stand and the body of Nelson was identified, having been shot seventeen times. Cowley took his own life to protect innocent Americans.

EPISODE #3 “THE OSAGE INDIAN MURDERS”

Broadcast on August 3, 1935

Plot: During the roaring twenties, the northeast Oklahoma town of Pawhuska was known as “Osage Monte Carlo.” Oil tycoons were common visitors to the Osage Indian Agency in Pawhuska. They came to bid for oil and gas leases on land owned by the Osage Indians. As a result, ten members of the extended family of Lizzie Q. Kyle were murdered between 1921 and 1923 for their headrights to oil royalties. A headright provided each Osage landowner an equal share of all mineral income, and could be inherited but not sold. In all, 20 killings occurred during what has become known as a “reign of terror: among the Osages. In 1929, three non-Indians were charged in some of the murders, including William K. Hale, a cattleman who had gained the trust of Osages and this is his life of crime.

EPISODE #4 “THE DURKIN CASE”

Broadcast on August 10, 1935

Plot: F.B.I. man Edward B. Shanahan had been assigned by J. Edgar Hoover to break up a stolen auto racket run by Martin Burkin, a well-known Midwestern operator. Durkin had a quick trigger finger, having wounded three policemen in Chicago, and one in California. Durkin, however, had worn his bulletproof vest, and the shots did him no harm. On January 20, 1926, a group of heavily armed agents in civilian clothing met at the train station before St. Louis. A G-Man knocked on the door and Durkin answered. They grappled with him, preventing him from reaching his gun. Thanks to the efforts of the G-Men on duty, Martin Durkin was finally captured.

EPISODE #5 “THE CANNON EXTORTION CASE”

Broadcast on August 17, 1935

Plot: This broadcast features the true events leading up to the F.B.I.’s investigation on known criminal Red Boyles, and his illegal activities. Thanks to cooperative citizens, agents of the Bureau were able to apprehend Boyles and have him sent to trial where he was found guilty and sentenced.

EPISODE #6 “THE BREMER KIDNAPPING CASE”

Broadcast on August 24, 1935

Plot: Edward Bremmer, a banker, was kidnapped by the Ma Barker – Alvin Karpis Gang, who demanded a $200,000 ransom. The father of the kidnap victim, Edward Bremmer, Sr., was a friend and political donor to President Franklin Roosevelt, who mentioned the kidnapping in one of his radio fireside chats. Within a few months of the kidnapping, agents of the Federal Bureau shattered and destroyed the Barker-Karpis Gang.

EPISODE #7 “THE URSCHEL KIDNAPPING CASE”

Broadcast on August 31, 1935

Plot: Charles Urschel was an oil tycoon of the “Black Gold” era. Two armed men, Machine Gun Kelly and Albert Bates (who was already wanted by the F.B.I.), had broke in on the card playing couples at the Urschel home in Oklahoma City and kidnapped the wealthy host. As soon as word reached the Bureau that Urschel was being held hostage in Missouri, the F.B.I. joined the search. Agent Gus Jones (former Texas Ranger) had been pulled from a lead role investigating the Kansas City Massacre, to head-up the agency in this case.

Trivia: The characters of Machine Gun Kelly and Albert Bates were not credited for the accomplished kidnapping during this broadcast. Instead, Harvey Bailey, commonly known as the “Dean of American Bank Robbers,” was dramatized as the guilty figure. Over the years, it has been discovered that Bailey was not involved with the Urschel kidnapping, making this broadcast historically inaccurate to date.

EPISODE #8 “THE CASE OF ‘MACHINE GUN’ KELLY”

Broadcast on September 7, 1935

Plot: George “Machine Gun” Kelly was the bank robber and kidnapping desperado who gave the federal agents their colorful nickname, “GMen.” Kelly’s crime sprees would launch him to the prestigious status of “Public Enemy Number One.” In July of 1933, Kelly plotted the scheme to kidnap wealthy oil tycoon & businessman Charles Urschel for a large ransom. He became known as the mastermind behind several of the successful small bank robberies Kelly pulled off throughout Texas and Mississippi.

EPISODE #9 “THE CASE OF THE TRI-STATE GANG”

Broadcast on September 14, 1935

Plot: On September 29, 1934, Tri-State gang members Walter Legenza and Robert Mais shot their way to freedom from the Richmond City, Virginia Jail while being accompanied to see their attorney. They shot two guards and mortally wounded a police officer. Police were ordered “shoot to kill.” On December 20, Mais, along with a band of robbers, held up a branch of the Philadelphia Electric Company and took $48,000 in cash. Federal agents caught up with the two gangsters and captured them in New York. They were returned to Richmond, Virginia on January 22, 1935 and their executions were scheduled for February.

EPISODE #10 “THE FLEAGLE FINGERPRINT CASE”

Broadcast on September 21, 1935

Plot: Brothers Ralph and Jake Fleagle were constantly coming and going to the family farm, convincing their family that they had done well in the stock market. What no one knew was they were really a gang of gunmen who were terrorizing the western states. Historians estimate that the Fleagles and their gangs were responsible for 60% of the heists in and around Kansas and California during the 1920s. Jake Fleagle made one fatal mistake. He left a single fingerprint on the car of Dr. Wineinger, one of their victims, and the print was identified as belonging to Jake, who had served time in the Oklahoma Penitentiary.

EPISODE #11 “THE CASE OF ‘PRETTY BOY” FLOYD”

Broadcast on September 28, 1935

Script written and completed on September 16, 1935.

Plot: Special Agent Raymond Caffrey, Detectives Hermanson and Grooms, Police Chief Reed, and their prisoner, Nash, lay dead. It was the bloodiest massacre of officers of the law in the history of American crime. Director Hoover mobilized a special squad to devote all of its time to bringing the murderers to justice. Attorney General Cummings announced that the atrocious challenge to law was accepted by the government – that Uncle Sam would not rest until the slayers were punished. Richetti and Floyd were the triggermen. Floyd was killed by the G-Men, Richetti was tried by court, sentenced and hanged.

Trivia: The Pretty Boy Floyd script was originally scheduled for broadcast on October 5. The reason being, Adam Richetti, one of its main characters, was scheduled to be hung on Ocober 4.

EPISODE #12 “THE BOETTCHER KIDNAPPING CASE”

Broadcast on October 5, 1935

Plot: One evening in 1933, as Charles and Anna Lou Boettcher returned home from a dinner party, they were accosted in their garage. Charles was held at gunpoint while another man passed a ransom note to Mrs. Boettcher. The kidnappers then sped away with Charles. The kidnapping was widely publicized locally and nationally. Charles was held for two weeks till the $60,000 ransom was paid. The tracing of the kidnappers through the underworld to a barber shop, and Mr. Boettcher’s extensive knowledge of flight patterns helped police locate the house in rural South Dakota where they were able to apprehend the kidnappers (Sankey and Banghart).

EPISODE #13 “THE CASE OF EDDIE DOLL”

Broadcast on October 12, 1935

Plot: Orphaned as a boy, Eddie Doll grew up in a Chicago slum and started his criminal career as a car thief, before he went on to bootlegging, bank robbing and kidnapping. Doll was in company with “Machine Gun” Kelly on two crimes, the first was the kidnapping of Howard Woolverton, a South Bend, Indiana banker on January 27, 1932. Later, on November 30, 1932 Eddie Doll, along with a few other Chicago hoodlums (including Kelly), robbed the Citizen’s State Bank of Tupelo, Mississippi of $38,000.

Trivia: Knowing he had something special soon after the premiere of G-Men, Lord enjoyed the fame his program received. “The tables were turned all right,” Lord publicly explained. “For the first time the public was seeing gangsters as they really are – drab cowards! The color and dash now had been usurped by the daring government men. The G-Men were giving all the thrills now.” The G-Men series rescued Lord from the plight in which he found himself after the failure of his world cruise on the “Seth Parker.”

In Closing

The series, however, lasted only 13 episodes before going off the air. Although the program went up to a Crossley rating of 22.5 at the end of ten weeks, Chevrolet optioned to discontinue the program because William S. Knudsen, President of General Motors, insisted on sponsoring a musical program. As a result, G-Men was replaced by The Chevrolet Show, featuring Dave Rubinoff and his Orchestra. Hoover, however, was in favor of continuing with the series and a promise was made that there would be enough cases to satisfy the Lord office, even if they were closed case files rather than active ones. Lord could see that participation for the G-Men series was thinning out. Hoover couldn’t let well enough alone. He wanted to control the story lines. The only problem was that Hoover had no dramatic sense and substituted scientific sleuthing for action and adventure.

Among Hoover’s suggestions for future programs was one about “A day or week in the life of an Agent.” For this parts of three or four good cases that have interesting sequences in them could be used and have the same Agent fictionalized as participating in all of them, thereby showing the diversity of crimes he is called upon to solve. Another suggestion Hoover made was “A Day in the Training of an Agent.” In the classroom, the training school, gymnasium, rifle range, crime-scene room (in which there is a body on the floor, for agents to examine, take fingerprints, etc.), and exposition of a fake kidnap raid.

According to Helen J. Sioussat, “They are certainly liberalizing a lot, aren’t they?” Hoover wanted to leave an image of the all-powerful “G-man” who hunted criminals and sleuthed with the latest technology which obviously appealed to the nation’s need for a strong, active government during the Depression. Hollywood, radio, the press, and comic strips played on this new image of the government agent.

“During the last few weeks of the G-Men series,” recalled Lord, “I became aware there were not sufficient F.B.I. cases and so I decided to change the title of the program and alter its form sufficiently to include police cases, district attorney cases, postal cases and all cases of law enforcement officers. As soon as I decided to make this change, I went to Washington and explained to Mr. Hoover why I wanted to make it. He was friendly about it, discussed it with me and suggested I concentrate on police cases, bringing in the F.B.I. only indirectly.”

This article features excerpts from Gang Busters: The Crime Fighters of American Broadcasting, by Martin Grams Jr.