|

| 77 Sunset Strip television series |

Remember 77 Sunset Strip? If you cannot remember the names of the lead characters, you no doubt remember Kookie and the finger snapping theme song. The first hour-long detective program to air on a weekly basis, the detectives worked hand-in-hand with the police... not insult them. Prior to 77 Sunset Strip, detectives and private investigators were depicted

on television as experienced men with service backgrounds and a not-too-favorable

relationship with the local police. These detectives were young, often seen smoking, drinking, having a taste for modern day jazz and a habit of

describing their female clients by their figures. In the same mold as Maverick, the producers chose to rotate the spotlight on the co-stars; one week Stuart Bailey might be the lead detective, another week Jeff Spencer. Sometimes they worked together, oftentimes they worked solo with brief appearances in the beginning or final moments of the episode.

Most of the episodes were pulp noir crime dramas, using such lingo as "gumshoe," "doll," "shamus" and "buzzer." Spawned housewives plotting to murder their husband's lovers, scamming insurance companies and a missing heiress was common. When the episodes centered on the solo adventures of Stuart Bailey (played by Efrem Zimbalist Jr.), the adventures oftentimes became high adventure and international intrigue. In many cases, Bailey was hired by the U.S. Government or met an old acquaintance from his old war days when he worked for the OSS. That's where "Secret Island" comes into play. On the evening of December 4, 1959, ABC-TV telecast the latest episode of 77 Sunset Strip, "Secret Island," which was either the worst -- or the best -- episode of the series to date... depending on your tastes.

The plot for "Secret Island" was a simple one. On route from Philippines with a wanted criminal, Stuart Bailey and five other survivors of a plane crash at sea reach an isolated island. Add a cheating husband and a woman with unscrupulous principals to the mix and Bailey finds himself with multiple tasks at hand besides finding a way off the island. When the men discover they are on the target of a future H-bomb test, they retain their information from the women. Young Lani finds evidence of the fact and withholds it from everyone but Bailey, who discovers the adults have been making a mistake of treating Barrie as a child. The radio provides the latest news of the test, including frequent updates of the on-coming plane designed to drop the bomb. After discovering how the test is going to be conducted, Bailey and the men use a reflection mirror to alert the pilot carrying the bomb and the test is postponed.

|

| 77 Sunset Strip comic book |

"Secret Island" was the 44th episode telecast in the series. Fans tuning into the program that evening expecting a mystery involving a double-cross, a femme fatale and murder might have been disappointed. Then again, episodes that do not follow the cookie-cuter format are often regarded by fans as the highlights of the series.

"Secret Island" was not the worst episode to air ("The Grandma Caper" in the first season was horrible) but it was not the best ("The Kookie Caper" aired weeks prior and is considered one of the ten best episodes of the series). But fans of the program continue to debate.

Personally, I prefer the film noir variety.

"Secret Island" was not the worst episode to air ("The Grandma Caper" in the first season was horrible) but it was not the best ("The Kookie Caper" aired weeks prior and is considered one of the ten best episodes of the series). But fans of the program continue to debate.

Personally, I prefer the film noir variety.

Among the

studio facilities was The Jungle, an exterior plot of ground complete with a

lake, tropical growth and enough trees to resemble

any time, setting or period from a wooded forest to the tropics. Most

of the filming for this episode took place in The Jungle but the first day of

filming was plagued with technical issues. Howie Horwitz, responsible for daily

television production, wrote a memo to William T. Orr on the evening May 8, explaining why

production was falling behind. “I don’t know if I am the only one who is having

this problem, but I seem to be running into the problem of faulty equipment

lately -- camera heads, belts, etc. For example, I have been delayed three

times (Secret Island) for a total of one hour and fifteen minutes while this

equipment was being repaired. The crews tell me there is no longer maintenance on

the equipment and if this is so, then perhaps something should be done about it.”

Under

george waGGner’s direction (yes, that is how the director preferred to have his name spelledin the closing credits), the entire production was completed on schedule

within the six days allotted for an hour-long television drama. Two weeks after

principal filming concluded, Horwitz sought permission from Hugh Benson to

shoot 3 or four additional lines of dialogue between Kookie and Roscoe, used

for the opening tag of this episode, which was already shot independently from

the rest of the program. “I can do this very easily,” Horwitz explained. “It

will require a couple of close-ups and george waGGner can shoot it during the

filming of ‘The Texas Doll’ next week.” His permission was granted and the

additional lines were shot and inserted into the rough cut.

Like every episode of the series

(and every Warner Bros. television production), numerous scenes were

complicated by outside interference such as planes flying overhead and

microphones that could not located close enough for the actors without being

visibly seen on camera. As a result, numerous lines of dialogue had to be

dubbed by the actors. On October 27, Horwitz wrote to Jim Moore, requesting a

rush job for what he felt was one of the best episodes of the series. “I know

the dubbing schedule is rough, but could we possibly get the 77 episode titled ‘Secret Island’

through a little ahead of time, as this is a particularly outstanding show and

we might want to have some advance screenings in order to raise some fuss in

the press.”

|

| (Left to Right) Kookie, Stu and Jeff on the Warner Bros. lot. |

Leonard Lee’s story idea was inspired

by an article he read in Newsweek magazine

documenting the accounts of atom bomb tests in the Pacific, either at Bikini or

Eniwetok, during the early fifties and involved a group of passengers from a small

pleasure boat instead of a commercial airplane and did not involve a detective

or a criminal. When Lee submitted his story to the producers of Climax and Playhouse 90, it was rejected. The author then proposed the idea to

producer Howie Horwitz. Howie liked it but Orr at first turned it down as being

too “off-beat” and not readily adaptable for the 77 Sunset Strip series. Horwitz pursued the matter, insisting it

would be a change of pace from the gumshoe approach and finally induced Orr to

agree to acquiring the story rights.

The

five-page story treatment titled “The End” was dated October 23, 1958, taking

place on board the boat. A formal seven-page plot synopsis of the same title

was drafted on April 7, 1959, now on board an airplane. In adapting it for Sunset, Horwitz and Lee in a story

conference agreed on some changes and additions. At Horwitz’s suggestion, instead

of the story taking place while Bailey is on a vacation, he goes out to the

Pacific to apprehend an embezzler for a surety company. Jack Emanuel suggested

to Lee that the story would have some better elements of Stagecoach or Five

Came Back -- where a group of people could be characterized. Sadly, while

the story offered the promise of strong and weak characters, human frailties

and love-hate relationships between the fictional characters and the viewers,

the final cut featured very little in the way of character development.

|

| Nancy Gates and Roger Smith |

In the end,

Leonard Lee was paid $500 for his short story, $1,230 for the first draft of

the teleplay and $770 for the completion of an acceptable final draft for a

grand total of $2,500. His contract for employment was dated March 26, 1959.

Just a few

weeks following the initial telecast, George Patrick Kelly (of Victoria, Australia)

sent a letter to Warner Bros. dated January 19, 1960, claiming “Secret Island”

infringed upon his copyrighted play, Suffer

the Innocent, which he wrote in 1956. On January 26 or 27, James Barnett at

Warner Bros. exchanged communication with Leonard Lee to verify that the author

had never seen nor had any knowledge of the George Patrick Kelly play. Lee even

registered his story with the Writer’s Guild of America (Registration Number

67079) on June 17, 1957. Barnett verified that Kelly’s play was never purchased

or considered by the studio. “The plot of ‘Secret Island’ is a generic one,”

Barnett wrote to Bryan Moore. “A writer conceiving such a basic premise could

only develop it logically along the lines that Mr. Lee followed.”

The finished teleplay was a somewhat expanded and adapted version of the original submission, and Lee was correct when he later swore, after being informed of the infringement, that he adapted it for 77 Sunset Strip with the help of producer Howie Horwitz who co-wrote the teleplay (un-credited).

Moore

conducted further communication with George Patrick Kelly and in a letter dated

February 25, Kelly acknowledged that his play was never produced or published,

but it was submitted to “a leading American Literary and Film Agent,” although

he could not disclose who this was. “I have requested our Foreign Department to

postpone any more exhibitions of our 77

Sunset Strip episode ‘Secret Island’ anywhere in the world, and I will also

request that it not be scheduled for rerun, until final disposition is made of

this claim,” Moore wrote to Parker Harris on March 4.

|

| Sue Randall and Edd "Kookie" Byrnes |

77 Sunset Strip was sold to the

Associated British Television Company in England, who in turn licensed it for television

stations other than their own. In a letter dated December 8, 1960, an attorney

named Tristam Owen, wrote to ATV stating that he represented Sydney Box Associates,

Ltd., the distributor of a film entitled S.O.S.

Pacific and that the 77 Sunset Strip was

so similar in plot that he felt there might have been a breach of copyright.

ATV referred him to ABC-TV, who referred Mr. Owen to Warner-Pathe Distributors,

Ltd., the British distribution company who distributed Warner’s theatrical

program, as well as television programs. Mr. Owen then wrote to Warner-Pathe by

letter dated January 3, 1961. During the month of January, the attorney in

England made arrangements to screen both S.O.S.

Pacific and “Secret Island” to determine if there would be a conflict.

Warner Brothers was protected since

“Secret Island” was covered under the Worldwide Errors and Omissions Policy and

for that reason the studio filed a claim to the Insurance Company so they were

aware of the situation. S.O.S. Pacific

was released theatrically in the United States in July of 1960. The writer’s

contract was dated March 26, 1959, and principal photography for the episode

was completed May 15, 1959, but the initial telecast was not until December 4,

1959, held back until the 1959-60 season although it was originally planned for

the 1958-59 season. This was the second claim they had on the picture.

At the time, television broadcasts

in Australia ran later than the United States airing and on different airdates

depending on the location: Sydney on January 8, 1960, Melbourne on January 15,

1960, Brisbane on June 10, 1960 and Perth on August 12, 1960.

|

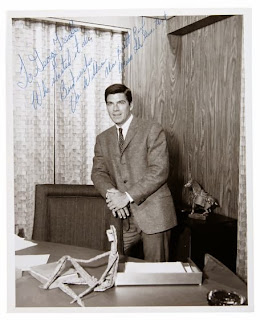

| Louis Quinn and Efrem Zimbalist Jr. |

By February 10, 1961, Owen had

viewed both the movie and the television episode. “I think that it is clear from

the viewing of the two films that the points of similarity between then were

more than could possibly arise from pure coincidence. In fact, I think I can

say that from the moment in the films when the passengers boarded the plane the

storyline of both films was almost identical and that, at one stage of the

development of the respective shooting scripts, there had been some material

which has been used as a source for both films.” Owen then swore in writing

that the script for S.O.S. Pacific

was written in 1955 and beat the studio to the punch. By August 1961, attorneys

for Warner Brothers had viewed both films and ruled: “It became apparent to all

who saw the two films that there were a great many similarities between them.

Some of these similarities were inevitable once the basic theme had been

devised, but others give rise to some suspicion at least that one story may have

been copied from another.”

Ultimately, an out-of-court

settlement was reached. Claims for infringement was not uncommon in Hollywood

and by 1960, more than a thousand television broadcasts had been subject to

similar claims. The fact that a studio settled on such claims did not mean the

studio committed infringement; such decisions were made based on the cheapest

approach since fighting an infringement case in court could cost more than the

settlement itself. In these cases, terms of the settlement were rarely

disclosed to the public but often allows the studio to continue syndicated

reruns of the broadcast and a statement that states the movie studio was not

guilty of the crime. Because the insurance company covered most of the

financial damages, the studio often considered an out-of-court settlement just

to get the claimant to go away quickly and quietly.

Fun Trivia

One of the two men communicating via radio during the test is Adam West, un-credited.

Actress Tuesday Weld was 15 years old when she appeared in this episode, which meant she was a minor and a welfare worker was required on the set: Gertrude Vizard. Weld’s character was originally called Lani in the first draft of the teleplay.

Blooper!

The words

“Phillipine Islands” is mis-spelled on the insert shot of the airport sign.

Production #2-6614

Episode #44 “SECRET ISLAND”

Final Draft of Script Dated: ________________

Initial Telecast: December 4, 1959

Dates of Production: May 8, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, 1959

Studio Production Shooting: The Jungle and Stage 19

Total Cost of Production: $61,408

Teleplay by Leonard Lee.

Directed by george waGGner.

Cast: Jacqueline Beer (Suzanne); Jacques Bergerac (Pierre D’Albert); Barry Cahill (the pilot); Joseph Conway (Chuck, the co-pilot, un-credited); Kathleen Crowley (Carol Miller); Jimmy Lydon (Steve, the navigator); Catherine McLeod (Amanda Connell); Louis Quinn (Roscoe); Joan Staley (the stewardess); Grant Sullivan (Dave Connell); and Tuesday Weld (Barrie).

Music Cues: Horsey! Keep Your Tail Up, Keep The Sun Out of My Eyes (by Walter Hirsch and Bert Kaplan, :04 and :05); 77 Sunset Strip (by Mack David and Jerry Livingston, :33); Fanfare (by Sawtell and Shefter, :06); 77 Sunset Strip (by David and Livingston, :42); In the Park (by Sawtell and Shefter, :26); Rainy Dawn (by Sawtell and Shefter, :54); Cosmic Man Appears (by Sawtell and Shefter, 1:00); Cosmic Man Destroyed (by Sawtell and Shefter, 1:33); Several Moods Dramatic #1 (by Sawtell and Shefter, 1:03); On My Way (by Sawtell and Shefter, :06); 77 Sunset Strip (by David and Livingston, :05 and :05); Beware (by Sawtell and Shefter, :11); Deep Trance (by Sawtell and Shefter, :43); Gentle Mocking (by Sawtell and Shefter, :40); Monkeying Around (by Sawtell and Shefter, :26); Gentle Mocking (by Sawtell and Shefter, :56); Hawaiian Eye (by David and Livingston, :20); More Far East (by John Neel, :25); Several Moods Dramatic #2 (by Sawtell and Shefter, :50); 77 Sunset Strip (by David and Livingston, :05); Cornered (by Sawtell and Shefter, :37); Several Moods Dramatic #1 (by Sawtell and Shefter, :27); Hawaiian Eye (by David and Livingston, :32); Religioso (by Sawtell and Shefter, :35); The Last Struggle (by Sawtell and Shefter, :30); Several Moods (by Sawtell and Shefter, 1:41); Leona (by David Buttolph, 1:00); Dead Reckoning (by Sawtell and Shefter, :19); Follow Him (by Sawtell and Shefter, :10); Wild Chase (by Heindorf, :33); Police Mystery (by Sawtell and Shefter, :20); The Monster’s Mate (by Sawtell and Shefter, :45); Great Raid (by Sawtell and Shefter, :17); 77 Sunset Strip (by David and Livingston, :38); Horsey! Keep Yout Tail Up, Keep the Sun Out of My Eyes (by Hirsch and Kaplan, :19); Blues (by Sawtell and Shefter, :10); 77 Sunset Strip (by David and Livingston, 1:10); and Fanfare (by Sawtell and Shefter, :04).

Licensed Music

Horsey, Keep Your Tail Up, Keep the Sun Out of My Eyes (Hirsch-Kaplan) Witmark, :04, :05 and :19