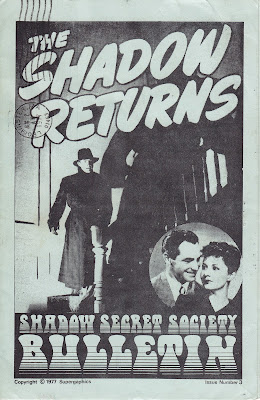

|

| Clara Bow, silent screen actress |

Hollywood celebrities participating on a radio quiz program was not uncommon during the forties. In 1946, when Jack Benny prompted an "I Can't Stand Jack Benny because..." contest, inviting radio listeners to submit the closing half of the statement, screen horror icon Peter Lorre was one of the three judges. (Ronald Colman read the prize-winning submission.) But when it came to stunts, you could look no further than Ralph Edwards and his quiz show, Truth or Consequences, which is regarded as one of the most popular audience participation programs of the forties. Little did he know at the time the program first premiered in the airwaves, on the evening of August 17, 1940, he would ultimately become host to one of the most popular sex symbols of the silent cinema.... Clara Bow.

Sponsored by the Procter & Gamble Company, Truth or Consequences originated out of New York City with Ralph Edwards as master of ceremonies and Bill Meeder at the organ. Participants were picked from the audience and on mike was asked a question. If the contestant answered correctly, they received $15. If they answered incorrectly, they received $5 -- but they must pay a consequence -- which was usually submitted by the radio audience. The best consequence act of the evening, as shown by the applause meter, won a $25 Defense Bond. Contestants who were chosen from the audience but did not get a chance to appear on the program received $2. Each contestant, whether appearing on the program or not, received five large cakes of Ivory Soap. (Procter & Gamble had to inject their product placement somewhere…)

Highlights of the program included the April 5, 1941 broadcast, which originated from Hollywood instead of New York City. During the program, Mrs. James Hays, winner of the Grand Prize in the Ivory contest, spoke a few words. On the August 2, 1941 broadcast, Martin Lewis, editor of Movie-Radio Guide magazine, presented a trophy from the magazine to Ralph Edwards for his program.

|

| Ralph Edwards at the radio mike. |

Beginning with the March 17, 1945, broadcast, Truth or Consequences originated out of Hollywood instead of New York. The format of the program also changed with the times, offering unique ways of awarding prizes to contestants. On the evening of December 29, 1945, Edwards began what was intended as a spoof of giveaway shows but soon propelled into a phenomenon. Each week a veiled mystery man, known only as "Mr. Hush," gave clues to his identity in doggerel. Edwards wanted Albert Einstein, who wasn't interested: he settled for Jack Dempsey, which took five weeks for a contestant to guess correctly. The pot built week after week, providing the winner of that contest a total of $13,500.

A subsequent "Mrs. Hush" contest began on the evening of January 25, 1947. The stunt was tied in with the March of Dimes. Listeners who heard the woman's voice and thought they could identify the owner of the voice could send their letters to "Mrs. Hush, Hollywood, California." (Back then the U.S. Post Office was able to deliver letters with such addresses. And letters were delivered almost overnight. Talk about the inefficiency of today's system!) Listeners were instructed to completed in 25 words of less the following sentence, "We should all support the March of Dimes because -----." Radio listeners had to make sure their name, mailing address and telephone number were printed plainly in the upper right-hand corner of the paper upon which their letter was written. They were also required to include a contribution to the March of Dimes. Any amount was allowed. From a penny to a $100 bill, submissions and donations poured into the Mrs. Hush office. While the donations were accepted, an estimated ten percent of the submissions were thrown out people listeners did not write their name and phone number clear enough to be understood. (Hey, sloppy handwriting is more common than you think.)

The radio announcer explained that two weeks from tonight, the writers of the three best letters would have a chance to answer a telephone call from Ralph Edwards and have a chance to identify Mrs. Hush. The prize for identifying Mrs. Hush was a 1947 Ford Sportsman Convertible automobile, a Bendix washer, and a round-trip ticket to New York City for two with a weekend reservation at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel while in the city. Who could not resist mailing a donation to the March of Dimes for a chance at that?

For every week contestants could not identify Mrs. Hush, three more prizes were added to the pot. It was requested of the radio audience not to include the name of Mrs. Hush in their letters -- that would be reserved for the phone call broadcast "live" on the air. Listeners could submit a donation every week if the contestants could not guess correctly.

Because the program was not transcribed and a repeat broadcast for the West Coast was "dramatized," the West Coast radio audience was instructed to be at the phone during the East Coast broadcast, in case they were to receive the call. Only one attempt would be made to reach the listener. On a technical side, before the radio contestant went on the air, a representative of the radio program sought verbal permission to re-enact the on-air conversation for the West Coast broadcast.

The judges in the contest were Federal Judge J.F.T. O'Conner, Roy Natiger, head of the Los Angeles County Chapter of the National Foundation of the March of Dimes, and Dr. Vierling Kersey, Superintendant of Los Angeles City Schools. This was for the slogan contest and the choosing of the contestants. Entries were judged on the originality, aptness of thought, and sincerity. (And of course, whether the handwriting could be read.)

|

| Clara Bow at the radio |

It was specified that Mrs. Hush could be from anywhere, and not necessarily from Hollywood. On the January 25, 1947, broadcast, Mrs. Hush read the following four-line jingle:

"Two o'clock and all is well;

Who it is I cannot tell;

Queen has her King, it's true,

But not her ribbon tied in blue."

A celebrity guest did assist with the January 25 broadcast, actress Louise Arthur, but she was not Mrs. Hush and that was clarified for the radio audience. For the February 1 broadcast, it was specified that any letters received through February 4 would be counted in the February 8 broadcast when Ralph Edwards phoned three lucky contestants. Letters received after February 4 and up through the next week would be used on the contest for February 15, etc.

|

| Clara Bow during the silent era |

On the February 1 broadcast, two of the famous Basenjis dogs, the barklessof Africa (Belgian Congo), were used in a contest. Ralph Edwards commented upon the growing popularity of the dogs as household pets in the country. He referred to the Magazine Digest January issue which had an article about the dogs. The dogs used on the program were flown in from the Hallwyre Kennels in Dallas, Texas. Three more prizes were added to the pot for this broadcast, even though Edwards did not call any contestants. A $1,000 full-length silver fox coat (provided by I.J. Fox), a Columbia Trailer, fully equipped and sleeps four, and a $1,000 diamond and ruby Bulova watch.

During the February 8, 1947 broadcast, the three people who were phoned had failed to identify Mrs. Hush, so three more prizes were added to the pot. These included a Tappan range, a Jacobs Home Freeze Unit packed with Birdseye Foods, and a 1947 RCA Phonograph-Victrola combination with 100 records. Edwards reminded the radio listeners that Mrs. Hush was heard from "Shang-ri-la," an unknown place somewhere in the United States. The remainder of the program had a "reducing stunt" in which two contestants were presented with $15 each and a card entitling each to take a special reducing course of 12 lessons at Terry Hunt's Health System on La Cienega in Hollywood. Also featured was a stunt titled "Baby Pig." The pig was presented to a contestant, complete with nursing bottle, diaper, etc. so the contestant could care for it properly.

The February 15, 1947 broadcast originated from the Golden Gate Theater in San Francisco. The voice of "Mrs. Hush" remained unidentified and once again three more prizes were added to the pot to hold over for the next week. These included an electric refrigerator, a vacuum cleaner with accessories, and a week's vacation for two in Sun Valley with air transportation both ways.

The program resumed in Hollywood with the February 22, 1947 broadcast. "Mrs. Hush" was again unidentified and three additional prizes were added: a Brunswick billiard table installed in the winner's home and complete with all sporting accessories needed to play the game; a $1,000 art-carved diamond ring designed by J.R. Wood; and a complete Hart Schaffner Marx wardrobe of clothes for each adult man and woman in the winner's family. There was a guest during the broadcast, Miss Clair Dodson, an Earl Carroll show girl, who assisted Ralph Edwards by entertaining one of the contestants.

|

| Clara Bow |

The March 1, 1947 broadcast featured a stunt whereby guest Dick Moorman, a veteran now working and trying to find a place to live in California, dictates a letter to his fiancee back in Long Island, New York… or so he thinks as he dictates that he will send for her so they may be married as soon as he rents an apartment or a house for them to live. Actually, the fiancee, Miss Gloria Minay, was the girl to whom he was giving the dictation. She was aptly disguised by Hollywood makeup artists who made her hair blond and used blue contact lenses to make her brown eyes appear blue. Gloria and her family were flown to Los Angeles and all expenses were paid by the producers of the program. In addition, the couple after their Hollywood marriage would be sent to Chicago where they would enjoy an all-expense-paid honeymoon in a Celotex pre-engineered home built by the Celotex people on Seventh Street next to the Stevens Hotel in Chicago. The trip to Chicago and back would be made on the Superchief and when the couple returned from their honeymoon, they would find a Celotex house waiting to be put up for them wherever they wanted to live -- the house would be just like the one in which they spent their honeymoon. Ralph Edwards told the audience that the house would be furnished with furniture as well. (When the contestant discovered that his fiancee was right on the stage with him, he said, "Oh, Christ!" which did not go over well with the network censors.)

The "Mrs. Hush" voice is once again unidentified and three more gifts were added for next week's program: an Oil-O-Matic burner completely installed with a year's supply of fuel, a Piper Cub airplane, and free maid service for one year. Due to a faulty line connection, at 8:54 p.m., the "Mrs. Hush" portion stopped momentarily and the two words, "has her," was lost over the air.

During the March 8, 1947 broadcast, "Mrs. Hush" was once again unidentified. Three additional prizes were added to the pot: a 144-piece china set, a typewriter, and a complete house-painting job inside and outside with Sherwin Williams paint.

Finally, on the broadcast of March 15, "Mrs. Hush" was identified. Mrs. William H. McCormick of Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, answered her telephone call from Ralph Edwards and she said "Clara Bow." Mrs. McCormick's winnings, valued at the time between $17,590 and $18,000, included: a 1947 convertible car, an electric washer, round-trip plane ticket for two to New York City with a week and a suite at the Waldorf-Astoria, a $1,000 full-length Silver Fox fur coat, a house-trailer fully equipped for four people, a $1,000 diamond and ruby wrist watch, a home-freeze-unit stocked with frozen foods, a Tappan gas range, a 1947 RCA Victor console radio-phonograph with 100 records, a refrigerator (Electrolux), a full-size home-billiard table with all equipment and installation, a furnace with a year's fuel supply to complete the home-heating unit; a 144-piece china set, free maid service for one year, complete house-painting job inside and out with Sherwin Williams paint, a typewriter, an all-Metal airplane, a week's vacation for two at Sun Valley, Idaho, with transportation both ways, a $1,000 diamond ring, an electric vacuum cleaner with all the attachments and a complete Schaffner Hart Marx wardrobe for every adult member of the immediate family.

Mrs. McCormick said she planned to divide her winnings with her neighbor, Mrs. A.H. Timms, and her sister, Mrs. William Harmon, both of whom helped identify Mrs. Hush. Following the identification, there was a pick-up from Las Vegas, Nevada, for the special guests: Clara Bow (Mrs. Rex Bell), who told about the way she was heard as Mrs. Hush every week, broadcasting from an auto park near her Las Vegas home. With Clara Bow, appearing on the program, was her husband Rex Bell, and her two children, George and Toni Bell, who never knew their mother was Mrs. Hush until this very evening. Clara Bow then told how she kept her identity known from her family, including the nearest neighbor who almost surprised her just when she was starting out to the "Shang-ri-La" where she made her broadcasts. Ralph Edwards told Clara Bow that he was sending her a special award, as a way of saying "thank you." A golden statuette, in behalf of the National Foundation of Infantile Paralysis, was going to be bestowed to Clara Bow as a result of the letters and contributions to the March of Dimes from contestants and radio listeners who sought to identify "Mrs. Hush." An estimated total of $400,000 was raised as a result of the contest. According to a representative of the March of Dimes, this was the largest single radio contribution ever received by the March of Dimes Fund. More than one million letters were sent in by contestants, each with a donation.

During the broadcast of March 22, the guests were Mrs. William McCormick and her husband. Having won the Mrs. Hush contest the week prior, she and her husband were flown to Hollywood for the broadcast. They talked about what they planned to do with the prizes. The McCormick family included three sons (the oldest was 14 and the baby was 18 months). The boys were back home listening to the broadcast. The evening's program featured a take-off called "Mrs. Hush's Mother-In-Law" in which the mothers-in-law of three contestants were hidden in the studio. Each told their in-laws what they thought of them but the in-laws had to identify their respective mother-in-laws. Another stunt featured a girl sent to the corner of Sunset and Vine to organize a Community Sing. She received one dollar for every person who joined her singing group. The program had a pick-up from the corner so listeners could judge the success of the singing group.

Later in the year, starting October 4, Truth or Consequences stopped re-enacting the repeat broadcasts and instead recorded each episode for later playback. This system was dropped in August of 1948 and then reinstated in August of 1949. The program made a quick jump to CBS under sponsorship of Pilip Morris, before returning to NBC for Pet Milk. The radio program expired in 1956.

The "Mrs. Hush" contest also served as a clever marketing ploy to promote the radio program. Numerous periodicals covered the contest, hoping to convince their readers to tune in and try to guess the identity of the mystery woman. Perhaps no other contest on Truth or Consequences gained such momentum until 1948, when the secret identity craze peaked with the "Walking Man" contest, which built to a then-fabulous jackpot of $22,500. That's right, folks had to guess who the mysterious man was simply by the way he walked. That man turned out to be Jack Benny.